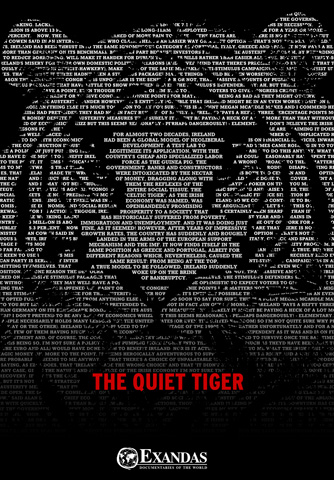

The Quiet Tiger

Dir: Yorgos AvgeropoulosFor almost two decades, Ireland had been a global model of neoliberal development. A test lab to legitimize its application, with the country’s cheap and specialized labor force as the guinea pig. The government, banks and constructors were intoxicated by the nectar of money, dragging along with them the reflexes of the entire social tissue. The “Celtic Tiger”, as the Irish economy was named, was openhandedly promising prosperity to a society that has historically suffered from poverty, immigration and unemployment. And it was doing just fine, as it seemed!

However, after years of impressive growth rates, the country has suddenly and roughly landed in the arms of the European support mechanism and the IMF. It now finds itself in the same position as Greece and Portugal, albeit for different reasons which, nevertheless, caused the same result: from being at the top, a true model to be followed, Ireland suddenly woke up on the brink of bankruptcy.

Watch the Film Now!

Choose the language you prefer and stream the film in Full HD from any digital device. Enjoy your private screening!

Buy the DVD

Public Screening

Are you interested in organizing a public screening of our film? Send us an email with your inquiry and we will be glad to assist you!

Educational / Library Use

Are you interested in enriching the library of your institution with our film? Contact us and let's create together an informed public!

- DURATION: 56min

- AVAILABLE IN THE FOLLOWING LANGUAGES: English | Greek

- AVAILABLE VERSIONS: English (56min) | Greek (56min)

- YEAR OF PRODUCTION: 2010

- Written & Directed by: Yorgos Avgeropoulos

- Produced by: Achilleas Kouremenos

- Production Manager: Anastasia Skoubri

- Director of Photograrphy: Alexis Barzos

- Research Coordinator: Georgia Anagnou

- Editing: Yiannis Biliris, Anna Prokou

- Original Music: Yiannis Paxevanis

PRODUCTION NOTES

Paradise for US high-tech multinationals. The country had one of Europe’s lowest tax rates for businesses, an English-speaking labor force, and the syndicates had agreed on “social truce” in benefit of the country’s development. As a result, Ireland displayed “Chinese” growth rates, as high as 8%!

However, the ensuing recession of the US economy and its interdependence with the Irish economy would cause a decrease in growth rates, a completely common and manageable effect. But the country’s government, ruled by party Fianna Fáil, considered it would lead to a loss of votes and, finally, of power. As economist Fintan O’Toole says: “The government wanted to avoid an economic recession, so they encouraged a new type of financial prospering, based almost entirely on real estate and bank services. It had nothing to do with people producing something and selling it, it was a typical financial bubble.”

So, the Irish economy grounded itself almost entirely on the construction industry. One amongst six Irish citizens was directly or indirectly employed by it. From 2001 onwards, the country resembled an endless worksite. Roads, railroads, buildings for all kinds of uses and entire neighborhoods popped up all around Ireland like mushrooms.

The cycle of construction and money was simple: the Irish banks would lend money with utter ease and low interest rates to any constructor who asked for a credit to build anything. They also handed out loans to any consumer who wished to buy a house. The Irish banks, in turn, borrowed money from other banks, mainly European, using the value of the landed property they had underwritten as coverage.

“There was absolute frenzy regarding real estate and anyone was able to go to a bank and withdraw money in order to buy a house. One could be absolutely certain that, within six months from the purchase, the house’s value would be doubled. There was a fit!” describes constructor Johnny Owens. “If you went to the local pub to have a drink, all you heard was: ‘What kind of an estate do you own? Where is it?’ Everyone was absolutely consumed by this situation, where we all ‘had to own property’!”

“Everyone felt we had a lot of money, we could do this, we could make more money, it’s that easy, there’s no way anything could go wrong, real estate never goes down”, says Suzan O’Callahan, who easily borrowed 1.2 million euro from banks in order to buy two houses. “There was a phrase in everyone’s mouth back then: ‘The only day a construction is expensive is the day you buy it, because after that it’s going to bring profit’. We believed it was like gold, that you could never lose your money”.

The US subprime mortgage bubble burst in 2007. The explosion was so strong it destroyed Lehman Brothers and the detonation wave crossed the Atlantic and struck the insular country. Ireland’s real estate market proved to be as unstable as the US market. Prices began to drop dramatically. And the oxygen tube that had been keeping the country alive broke. Bank properties lost their value. The loans, which had once been given out openhandedly, now stopped, consumers were discouraged, the construction companies found themselves owing a lot of money to the banks and began to shut down one after the other.

The Irish banks, which could not return the money they had borrowed from the European banks, asked the State for its help. And the kind State rushed to their aid using the money of tax-payers. It nationalized the banks in 2008, transferring their huge debts to all Irish citizens. “When business is good, the Markets tell the State to sit back and let them do their thing. However, when things go wrong, the Markets want an interventionist State who will save them”, observes economist Fintan O’ Toole. “These are just guys who went to the casino, put their money on the table, won a few rounds, went crazy and considered they would continue to win, lost and then went to the garage and told the guy who washes their car: ‘Here is the bill, you will pay my gambling bet’. That’s what is going on in Ireland.”

“We do not put money in the banks for the sake of the banks”, refutes Dara Calleary, a minister of the government at that time. “By supporting banks we guaranteed their future, and through guaranteeing their future we also guaranteed credit for our businesses and consumers, and we also guaranteed the people’s savings”.

So, Ireland suddenly found itself with a huge black hole in its economy. One of the collapsing banks alone, the Anglo Irish bank, gobbled up 35 billion euro of State help, an incredible 22% of the country’s GDP. Naturally, in order to cover the enormous debt of the banks, that had now become the debt of the State, the government immediately took harsh measures. Ireland was the first country in the EU to apply severe austerity measures, with the unlikely target of reducing the country’s deficit from 14% to 3% by the year 2014. Salaries and subsidies were butchered. Unemployment was multiplied by three.

The country once again became a model, but not as the hen that lays golden eggs but as a pioneer in “financial rationalization”, as the IMF representatives said, applauding the government’s actions. “The Irish establishment became obsessed with being ‘well-behaved’, with acting the way that the EU, the IMF and the international markets wanted”, says Fintan O’ Toole. “They did everything they were supposed to do. They decreased public expenses, they attacked public services, reduced people’s salaries, guaranteed the bank debts, they followed the international agenda to the letter. And what did they get in return? Nothing! The result was disastrous.”

Ireland had not made it. In November 2010, the country urgently asked for and acquired 85 billion euro from the IMF and the European support mechanism. “Although they behaved exactly as they were supposed to, instead of having their heads condescendingly patted, instead of being rewarded, instead of having the markets – those almighty markets – say ‘Oh, you are such good boys, here, have some sweets’, the markets said: ‘We don’t believe you! Since you are cutting back, your economy will fail, so we cannot give you money’. I believe that Ireland should be considered a good example of what happens when you are a good boy. If you are a good boy and expect to be rewarded, the Irish affair says it is not going to happen”.

Today, the shadow of the Celtic Tiger wanders around the hundreds of abandoned settlements built during the past decade. In the empty, uninhabited neighborhoods. In the lifeless, imposing buildings of Dublin and the malls that are still awaiting their clients. In the new, ultra-luxurious airport, a symbol of opulence and financial prosperity, which no one uses. And in the impressive Aviva Stadium, where the first big event held was a congress on prospects of immigrating abroad. It was filled by thousands of young people from all around the country.